|

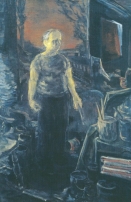

When someone once asked John Lessore if he had any particular interests outside of painting he replied 'none that he could think of', and it was pointed out to him that this must be a rather narrow, limited outlook. After thinking about it for a while, he simply replied that 'yes', he supposed it was. Obviously, he has the relations with family that are important to all of us, but in the time I have known Lessore what we most often discuss is painting, whether it be his or other art. He is a man who was brought up around painting. His Mother, Helen Lessore started the legendary Beaux Arts Gallery in Bruton Place, the birthplace of the 'School of London'. He has it in his veins (his uncle was the great Walter Sickert), many of his friends are painters (he has been sitting for Leon Kossoff almost every Wednesday for over forty years) and when he travels, it is the paintings in the museums that interest him most. John Lessore is in some ways an extremist. Everything about him betrays this; he is a soft-spoken man, not pushy or demanding, although I suspect a firmness bordering on the stubborn when it comes to his work. He is a Trustee of the National Gallery in London with a keen interest in conservation, has a large family and travels to a house in the South of France and a cottage he owns in Norfolk often to paint. A glance at the reproductions in this catalogue certainly does not indicate a man who sets out to shock in any way - there are no sharks in formaldehyde here. He describes his paintings as 'gentle and contemplative'. They are almost musical constructions with simple, often domestic subject matter and do not appear full of angst or personal expressionist emotion. However, this is also a man whose entire life is devoted to painting and its history, and with a few others of his generation or slightly older in London he has, perhaps unwittingly, taken what is in my view an extreme position in contemporary art: the view that in painting it is all there if you have the eyes to see it - that no other medium allows such depth of expression, whether the quarry be emotion, psychology or philosophy than painting. Nowadays, in an era of new media, art stars, shock value, an art world and bureaucracy of behemoth proportions and shorter attention spans, this is more than simply a pointed view but a focus so rigorous that Lessore may be considered, if not extreme, then certainly the exception as opposed to the rule. The studio in Peckham in London is worth mentioning at this juncture in order to shed some insight on the artist. Upon entering his studio the first thing that struck me was the relative lack of light. Natural light only enters from the window to the street and at the other end of the room, from a small window on to the garden area. It is worth noting that Lessore also has studios in the Midi of France and in a cottage in Norfolk where the outside light is very different. The London studio is not large and airy, but compact and almost confined. The idea of a laboratory comes to mind and indeed that is what it is - a place where Lessore sorts out pictorial problems - an alchemist if you will. There is a corridor to the left stacked full of boxes (old catalogues) which leads to a storage area equipped with racks where old works, discarded or unfinished works and sometimes even works in progress are stored and may be seen with some difficulty. The house he lives in, within walking distance, has some of the same feeling. A cacophony of his own work and works by relatives and friends line the walls in an almost studied atmosphere, which at first brings to mind a gentle neglect. In fact nothing could be further from the truth as I found out for myself when I queried him about individual pieces. They all have stories attached to them and are a significant part of his daily life. Drawing is critical to Lessore when discussing the work. He considers himself fortunate to have attended art school when it was still conventionally taught. He does not consider his drawings as things in themselves or finished artworks but rather a means by which to retain the memory of a moment that might otherwise not be retained, or not in the same way, and the sketches are kept as diary elements to be referred to later if and when they are needed. They may not necessarily come from life; they may just as easily have come from a Velasquez or a Degas. His paintings display the touch of a superb draughtsman and this ability to draw allows him to explore the architecture of his chosen scenes with relative ease. Lessore does not paint often directly from the subject, a fact that puts him at odds with some of his peers, but rather, alone in his studio using his sketches and memory to construct his paintings. The working process is rigorous and regular but entirely unpredictable in terms of output. Lessore does not work solely on one until it is finished but works on a number of canvases, of different shapes and sizes at the same time. A painting may be conventionally 'finished' to a visiting eye like my own and then be put away for weeks, months, and even years before it is brought out again and confronted by the artist. Thus there are no conventional 'periods' or at least they are less defined in comparison with many artists whose work may be seen to significantly change from show to show. A work done in 1985 or started in 1985 and completed in 1995 may fit perfectly in its resonance with something painted relatively quickly only last year. Lessore's process is to go back to the painting again and again - there is no timetable - until it 'works'. This exhibition itself was subject, I see in retrospect, to some of the same modus operandi. I was impressed with Lessore's sell out show at Theo Waddington in London in 1997 and we first discussed this project in 2001, but for one reason or another, it was postponed a couple of times until this year. This did not seem to bother Lessore at all; even relatively last minute date changes he took in his stride and told me the exhibition would happen 'when the time was right'. I see now that this is similar to his way of painting. Don't rush it; go back to it again and again. Lessore has stated that 'every painter thinks about light in different ways' and as Martin Gayford has pointed out, to him it resembles a liquid. Lessore wonders if his whole life has been affected by a phrase he read when he was young about Titian's paintings being 'bathed in golden light'. He goes on to say that the source of the light remains enigmatic. I agree. Technically, for me it is not clear how much is coming through from the ground and how much is from the colours and the use of white but the end result is that when I leave the studio and conjure a picture up in my minds eye, it is the light which I recall most clearly. Whether it be a burnt umber, a yellow or a more sombre grey, Michael Peppiatt is right - these paintings actually gleam - and for me it is the light which gives them their magic and allows them an ongoing space in the mind of the spectator after the experience of viewing. The paintings have an extraordinary clarity of composition. The working method of returning to the canvas and constant re-appraisal, perhaps shifting the figures or changing the position of a limb or the tilt of a neck, must be a laborious process but in the finished works none of this prior struggle is evident. Like Matisse, who drew for a couple of hours a day in order to hone the skills that allowed him an economy of line that make the drawings and etchings look so easy, the finished paintings of Lessore never look forced and evidence of the labour is absent. His quarry is to find a flow in the composition - and music comes again to mind here - where the finished picture has no rough edges, no noisy interruptions. It is as though he finds a 'key signature' somewhere along the way and settles the painting into that flow, whether it be a quiet interior in the Midi of France or a comparatively high pitched street crossing using the colour and drama of the streets of Peckham as inspiration. Either way, every brushstroke is important and supportive of the next; there are rarely passages that outweigh others in importance. The result is that the paintings draw you in and at times I find myself equally interested in the table around which figures may be sitting as the figures themselves. At other times, I am drawn only to the surface: the paintings can look nearly abstract such is the democracy of brushstrokes, and I watch as the figures recede into an architectural, minimal and sometimes quite severe composition. A single note, visceral and to the body. When the figures return and I study a glance or a gesture, my mind kicks in and the human relations and the psychology of the scene raise the tempo to an almost symphonic level. A great deal of this depends on my own state of mind, but the important thing is that the contrasts are there, sometimes quite obvious and sometimes embedded deep within the picture. Over time an incredible richness emerges. There is something strangely familiar in the paintings, a remarkable accessibility. The interiors from which most of the paintings in this exhibition derive their subject matter are of course familiar in some way to all of us. We all have families, kitchen tables and live somewhere. Sometimes an aspect of the subject matter derives from art history, which may strike a chord within us whether consciously or not, as Lessore looks to the history painting of the old masters to solve complex problems of interlocking figures. The psychology of the paintings and sometimes the space remind me of Degas, particularly the BELLELLI family in the Museé d'Orsay, and it would surprise me if the artist does not count Degas as a major influence. Whatever the reason, the paintings have a remarkable intimacy which is mysterious to me in that some of them almost seem to greet me as old friends and although I cannot recall the circumstances under which we 'met' and the 'friendship'' flourished, it is clear and palpable. Through externalizing his own inner world in the paintings he is able to illuminate mine. The man himself is like this. I felt early on that we had some shared past which is not logically present beyond a mutual interest in art and perhaps my familiarity with his face in Leon Kossoff paintings I have or have had in the gallery, so perhaps this uncanny ability to project familiarity in the paintings is also an extension and characteristic of the artist's personality. The subject matter has been called unremarkable. The results are not. A group of people sitting around a table, someone asleep, a chair study or a woman standing in a studio. Some of the 'French' paintings may feature a couple strolling along the beach. Other figures may be crossing the streets around Peckham at night. It seems that Lessore looks at life as a succession of 'moments' (in Zen philosophy an inarguable truth) and he is lucky enough to be an artist and find these moments all around him. When he leaves his door for the short journey to his studio, he knows not what will catch his eye. The light on an ambulance following a minor bicycle accident, the scaffolding on a building, a sudden break in the weather on an overcast day which bathes an otherwise unremarkable bridge in a glorious light. With this approach, anything can happen on a given day, and whether there is a painting germinating or not, there are memorable moments in the ordinary all around all of us if we choose to have the eyes to see. These moments, (or as Peppiatt calls them, 'clusters of moments') are transformed into paintings that are both diary and laboratory. For me the extraordinary thing is how Lessore's vision allows me to see similar scenes in my own life differently, to be on the lookout so to speak, because every day has the monumental in the minutiae. Life is random. – Bill Gregory Seal Rocks NSW August 2005 © Annandale Galleries |